Supplication & Splatter Horror: Taurus Decan III

By Joey Cannizzaro

Be advised that this piece contains violent content.

I wanted to write about the third decan of Taurus because it scares people.

While most people with natal placements in this part of the chart won’t experience its most extreme manifestations, for astrology to be a complete language it has to include the intense, frightening, even violent energies that exist in the world and the cosmos. Being with fear is one way to spend time with Saturn, the ruler of this decan, and while it may sound like a contradiction, I hope this piece shows some of the ways that Saturnian things, like mourning, strife, or suffering, can also be a source of real power in the struggle for both personal and political liberation.

In researching the decan, I’ve become fascinated by a transit to this part of my own chart: my brother has his sun at 26° Taurus, while I have Jupiter and my Lot of Fortune at the same degree; I was struck by a memory of his 17th birthday, when I was supposed to go with him to his birthday party, but decided not to get in the car at the last minute. On the way there, he had a violent car accident; he was fine, but the passenger seat of his vehicle was obliterated. If Jupiter and Fortuna hadn’t intervened I would have been, too. When I looked at the astrology, I found that his birthday that year was the day after an eclipse exactly on his sun, and my jaw dropped seeing the sun rising on the ascendant at the exact moment of the solar return.

From the Hellenistic perspective, the signs are understood more like different lands with their own natural resources and culture, while the rulerships tell us what kinds of deities this land has, and which metaphysical energies are central to their worldview. Taurus III is the first decan in the zodiac assigned to Saturn, the greater malefic. The entire sign of Taurus is still the world of Venus, but this particular locality is heavy with Saturn’s dark gravity, his preoccupation with control and limitation, and his often brutal approach to showing us how suffering can make us indomitable. The degrees 20 - 30 Taurus also have malefic rulership by bounds: only the first 2 degrees are ruled by Jupiter, followed by 5 degrees ruled by Saturn, and the final 3 by Mars. I noticed that even the dodecatemoria of Taurus III are only signs from the winter solstice to the spring equinox, making the final decan a little microcosm of the coldest, darkest part of the year, somehow right in the middle of the new life and warmth of spring.

Beyond rulership, Taurus III also has a menacing reputation because it’s the home of perhaps the most notorious fixed-star, Algol (from Arabic رأس الغول raʾs al-ghūl or “the demon’s head”) at 26°. It’s the most prominent star in Medusa’s decapitated head, and so has come to be associated with actual beheadings, sudden and violent events, fear and rage. Yes, there are some interesting historical correlations between this decan and assassinations or executions, but most people’s lives aren’t all that dramatic (if this is stressing you out, maybe take comfort in that!). I’m interested in unpacking how a decan layered with such extreme energy can resonate with us now, on various scales of experience, and what makes Taurus III distinct from the sum of its rulerships and fixed stars.

I think it’s tempting to take for granted that the decans can be transposed onto natal interpretation and treated more or less like the other planetary rulership schemes. However, their use in Egypt was mostly for timing religious rituals or performing acts of magic, and their rulers weren’t taken into consideration in evaluating planetary conditions until the Medieval period. One of the most consistent uses of the decans has been identifying and communicating with daimons, semi-divine beings that act as intermediaries between the gods and human beings. The decans weren’t just a section of sky and stars, “They were personalized entities with names, physical features, and healing or, conversely, malevolent powers over their dominions, which had to be summoned or else averted, often by means of amulets.” (Decanal Iconography and Natural Materials in the Sacred Book of Hermes to Asclepius. Piperakis, Spyros.)

The scattered historical information and often opaque descriptions of the decans in older material reflect their esoteric nature; what if we treat them more like independent demi-gods and less like representations of human psychology? How are they relevant to us as practitioners of astrology and what do the historical transmissions we do have to tell us about how to propitiate, connect with, and develop a relationship to these arcane forces?

There are four distinct figures, different daimons, compressed into the third decan of Taurus. The first three are more loosely defined and mysterious; their descriptions alone are much of what we know about them, but they have this arcane opacity that seems numinous.

1. Hrômenôs (Sacred Book of Hermes to Asclepius. Egypt, 1st century BCE)

“Its image is that of a dog-headed man with curls on his head. In his right hand he holds a sceptre and his left hand touches his buttocks. He wears a belt that falls at his knees. He rules the mouth and throat. Engrave him on a hyacinth stone and place a bugloss plant under it, enclosing the whole in a gold or silver ring and wear it on you. Avoid eating eel.”

2. Sphendonael (Testament of Solomon, started 1st century CE, completed Medieval)

In the book Testament of Solomon, an apocryphal text ascribed to King Solomon, the 36 decans appear as daimons, whom Solomon summons to learn their names, what they do, and how they can be quelled. The daimon associated with Taurus III is Sphendonael. He’s said to have had “a shapeless head like a dog with a face like a bird, donkey, or ox. He causes tumors of the parotid gland and tetanic recurvation (the body bent backwards rigidly) and is quelled by the words ‘Sabael, imprison Sphendonael.’” (Encyclopedia of Demons in World Religions and Cultures. Bane, Teresa).

Notably, the recurvation of the back caused by the daimon of this decan has become the most iconic image of demonic possession. This pose, the “arch of hysteria,” was gendered and pathologized by early psychoanalysts; look at the 19th-century neurologist Charcot’s drawing below, what he calls the “Arc de Cercle,” an obvious visual influence on The Exorcist.

3. Long-toothed elephant man (Picatrix / Ibn Ezra, 11th and 12th Century CE)

Many of the later descriptions of the decan crystalize around an unsettling, miserable figure with his long white teeth. The 11th-century grimoire, the Picatrix, which preserves many older astral magic traditions, describes him as “a man of ruddy coloring with large, white teeth appearing outside of his mouth, and a body like an elephant whose legs are long; and there ascends with him one horse, one dog, and one calf. And this is a face of laziness, poverty, misery, and fear.” Ibn Ezra evokes the same figure in the 12th century: “A man whose feet are white and so are his teeth, which are so long that they can be seen outside his lips. His complexion is reddish and so is his hair, and his body resembles that of an elephant and a lion, and he is not reasonable, and all his thoughts are toward evil, and he is sitting propped up. There also ascends a horse and a dog, and a small calf.”

4. Litai (Liber Hermetis, as old as the 2nd century BCE)

The Liber Hermetis, which preserves hermetic astrological practices going back as far as the 2nd century BCE, ascribes the 3rd decan of Taurus to the Litai.

The Litai are the counterparts to Ate, an ancient Greek goddess who personifies ruin; Hesiod says she’s the daughter of Zeus and Eris (Strife). Ate never walks along the ground, only across the heads of mortals, possessing each person she steps on with delusion, recklessness, and disaster. Her sisters, the Litai, follow behind her bringing relief and repair, but they are elderly hags with malformed feet, who can never catch up to the maniacal dance of Ate. They don’t only heal; they also devastate those who don’t atone after being possessed by Ate.

In contrast to the other daimons of Taurus III, the Litai are pretty well-documented and defined mythological figures, mentioned in both The Iliad and The Odyssey. Their name is usually translated as just “prayers,” but I want to flesh out the archetype by analyzing what kind of prayer they represent since the word prayer alone can mean almost anything and end up feeling hollow.

In Richard Lattimore’s translation of The Iliad, the word supplication is used to describe the prayers of the Litai. It’s employed twice: humans supplicate themselves to the gods to appease them and relieve the suffering left in the footsteps of Ate; the Litai themselves go to Zeus in supplication and ask him to bring ruin on those who don’t offer them prayer. If this is how you pray to the Litai, and this is the way the Litai pray, it’s important to understand what supplication is and what makes it distinct from a more generalized notion of prayer.

Supplication is the act of surrendering your pride completely and begging for mercy. In ancient Greek culture and literature, its most recognizable posture involves clasping the arms around the knees of the person, or representation of a god, that is being supplicated. It’s a public performance of the renunciation of dignity. Hellenistic interpretations of the 3rd decan of Taurus echo this idea. Among a long list of miserable outcomes for planets there, Hephaistio includes the delineation that “they will set aside their dignified facade.”

Because isn’t dignity a facade? Perhaps the kinds of harrowing experiences associated with the decan help to unchain us from dignified and polite behavior. To be someone who sets aside their dignified facade could mean embracing being cast as the other, finding belonging in abjection, among the outcast and rejected. It’s no coincidence that the Litai are disabled, slow, a collective, acting responsively to Ate’s individual, senseless dance of ruin. In the third decan of Taurus, we’re called to get on our knees and stop caring about our reputation and what respect we might lose in the eyes of the normative when we grovel in the wake of the impossible void of ruin after it sweeps through our lives.

Anyone who has had to recover from a collapse knows that you often have to do things your old self would find embarrassing; the performance of rituals can feel cloying or unnatural to start. Supplication is the act of doing actions to try and rebuild, no matter how ridiculous or demeaned we may feel doing them.

Ancient Greek representations of supplication will ring true for many who have had psychological episodes that ableist culture would label hysterical. In Gaye McSweeney’s Acts of Supplication in Ancient Greece, he describes the way clasping of the knees was elaborated on in the act of supplication:

“The clasping of the knees may be accompanied by other gestures…such as the laceration of cheeks, the eyes pouring with tears, the beating of breasts, tearing out the hair and the wearing of clothes more appropriate for mourners.”

These same supplicating gestures formed the first phase of the mourning ritual for the recently deceased:

“The preparation of the body for burial was marked by the violent expression of grief, performed by the women closest to the deceased. In this phase, the women would wail, beat their breasts, tear their necks, faces, hair and breasts, disarrange their clothes, and fling themselves onto the corpse.”

In their essay Soft Blues—a piece about madness, patriarchy, and hubris—Johanna Hedva writes about being forcibly interned in a psych ward by an ex-partner for mourning their miscarriage in exactly this way. Within the culture of carceral neoliberal capitalism, supplicating the Litai with the appropriate level of abandon—whether we’re mourning the dead or another loss—is in itself an act of criminal dissidence that has to be suppressed. What power that gives to the act.

McSweeney argues, that the violence of the supplication part of the mourning ritual may also have had a more radical social function in “preparing people for the exaction of revenge…Elektra and Orestes, with the chorus, indulge in a protracted lament for the dead Agamemnon. This… has the effect of creating the group solidarity and anger that is needed for revenge against Agamemnon's murderers.”

This resonates with the argument made for ultra-violent horror films in the book of political theory Splatter Capital: The Political Economy of Gore Films—that one of their functions is to embody the extreme violence that is already (and often more invisibly) perpetrated every day by states and global capital, and in doing so provoke an openness to the level of responsive violence that characterizes actual uprisings.

If we think of the Litai as a kind of embrace of the power that comes from having profoundly suffered—a new connection to the gods made through the intermediary of the Litai who arrives only in Ate’s wake—then the connection between supplication and revenge feels even more compelling. Even the post-Homeric Greek epic poet Quintus Smyrnaeus connects the Litai to the Erinnyes or Furies—the divine embodiment of vengeance—calling them, “the daughters of the Thunderer Zeus, whose anger follows unrelenting pride with vengeance, and the Erinnys execute their wrath.”

This understanding of supplication adds another level to the political dimension of the third decan of Taurus that is already evoked by the head of Medusa and its association with the act of beheading. Beheading is a political act in a way that not all acts of violence are. The guillotine, specifically, is inseparable from the symbolic removal of centralized command of the social body, an icon of violent uprising against the elite and political leadership so much so that on social media guillotine emojis and gifs are used by communists and anarchists as shorthand for the (half-joking) call for the rich to be decapitated. Both Bakunin and Marx have the planet that rules their sun in the third decan of Taurus.

In Ovid’s telling, Medusa is herself a living revenge against the patriarchy. Before becoming a monster, she was a beautiful, mortal woman who was raped by Neptune in Minerva’s temple. Instead of blaming the rapist god, Minerva punished Medusa, transforming her into a horrifying gorgon who turned anyone who looked at her into stone (a very Saturnian superpower). Her punishment may have been sickeningly unjust, but it made her a supernatural force of obliteration.

The Litai remind us that the fury of mourning is explosively powerful, perhaps an unstoppable force. Remember that there are two sides to the Litai and their decan: acts of supplication, extremes of emotional release and surrender, are what appease the Litai and relieve suffering; but the Litai don’t only bring healing, they also decimate those who don’t supplicate themselves in the face of tragedy, and those who refuse to atone when they’ve been the possessed by Ate, delusional and destructive. It’s hard not to think of the genocide that Israel (a state with their sun at 23 degrees of Taurus) is committing against the Palestinian people as we speak, and the hubris that makes them think the righteous anger of their victims can be ruthlessly suppressed and contained, as if it won’t recoil back on them with equally brutal force. The Litai bring ruin on those who revel in the trail of gore left by Ate, mocking supplication and atonement.

It feels important to resist a conservative, moralistic reading of this decan, as though it punishes you for sinning, and somehow praying to god and feeling guilty is what brings realignment. The horrible things that happen to us are so often more like the erratic footsteps of Ate, not our fault at all, and not a lesson for us to learn, but experiences for us to draw power from nonetheless, the power that comes from surrender, from abandoning composure. It’s not the decan of Ate but of Litai. You defy them and call down their vengeance not when you make delusional mistakes, but by clinging to pride and the performance of dignity in the face of collapse.

Maybe a malefic decan isn’t so bad if you belong to the maligned; the Litai could be the daimonic ally we can call on, not just to ask for the fortitude to survive the brutality of Ate, but to help us abandon ourselves to the hysterical force of supplication, and unleash destruction on those who refuse to mourn or atone when faced with the carnage of their own actions.

About the Author

Joey Cannizzaro (they/them, she/her) is an astrologer, artist, and teacher. Across disciplines and forms of media, they work with metaphysics to cultivate radically different ways of thinking & being. Joey’s astrology practice is oriented towards both nurturing personal liberation & provoking societal transformation, weaving together Hellenistic techniques & ancient cosmology with threads of anarchism, mysticism, crip theory, and queerness. They hold a certification in Hellenistic Astrology from Demetra George, a bachelor's degree from The New School, and an MFA from California Institute of the Arts.

Website to book a reading or find their blog: ChronosAndChaos.com

Instagram: @ blimpsecretions

Read their essay "High Priest of Mass Data, or Surveillance is Just Astrology for White Men" at COVEN Berlin.

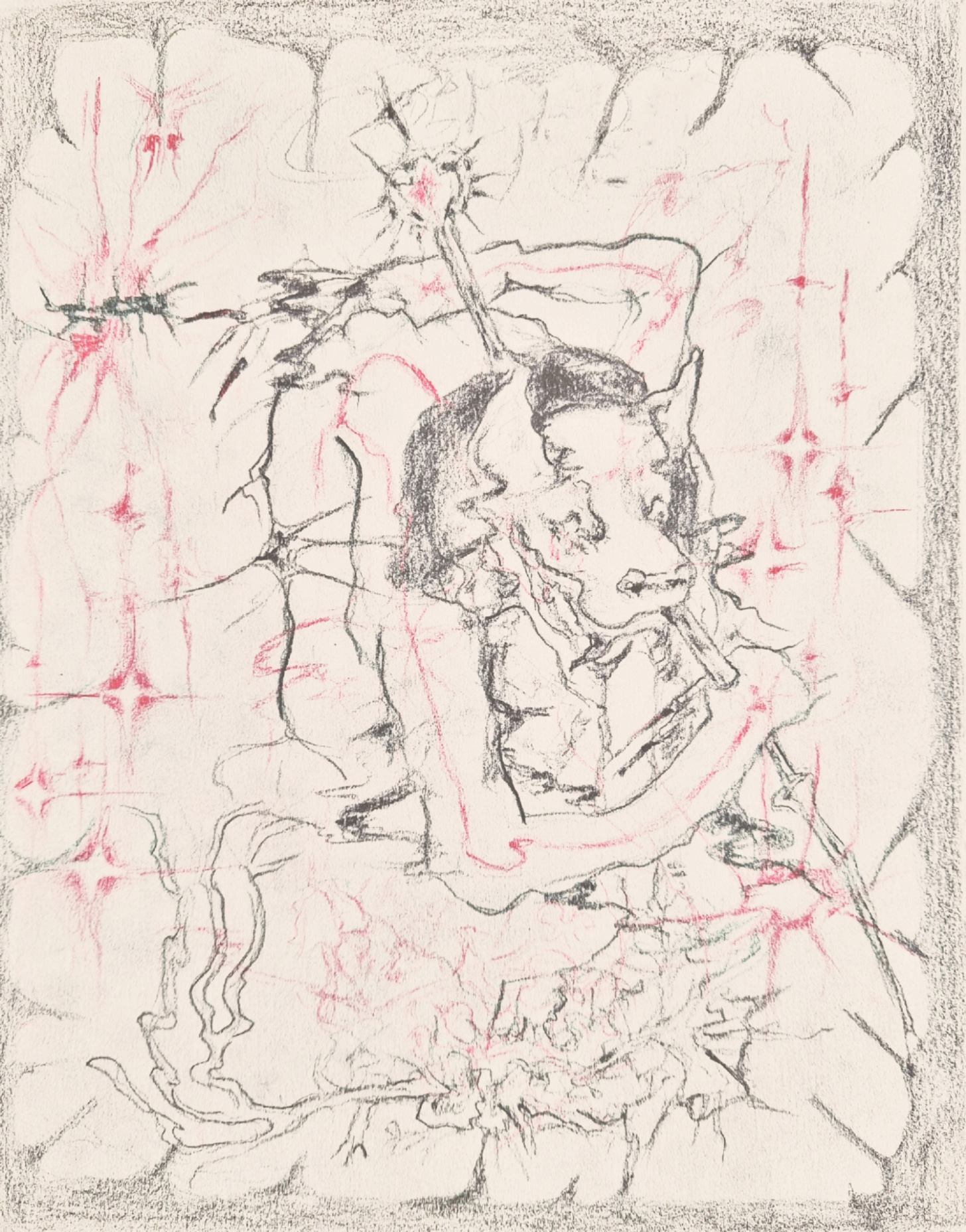

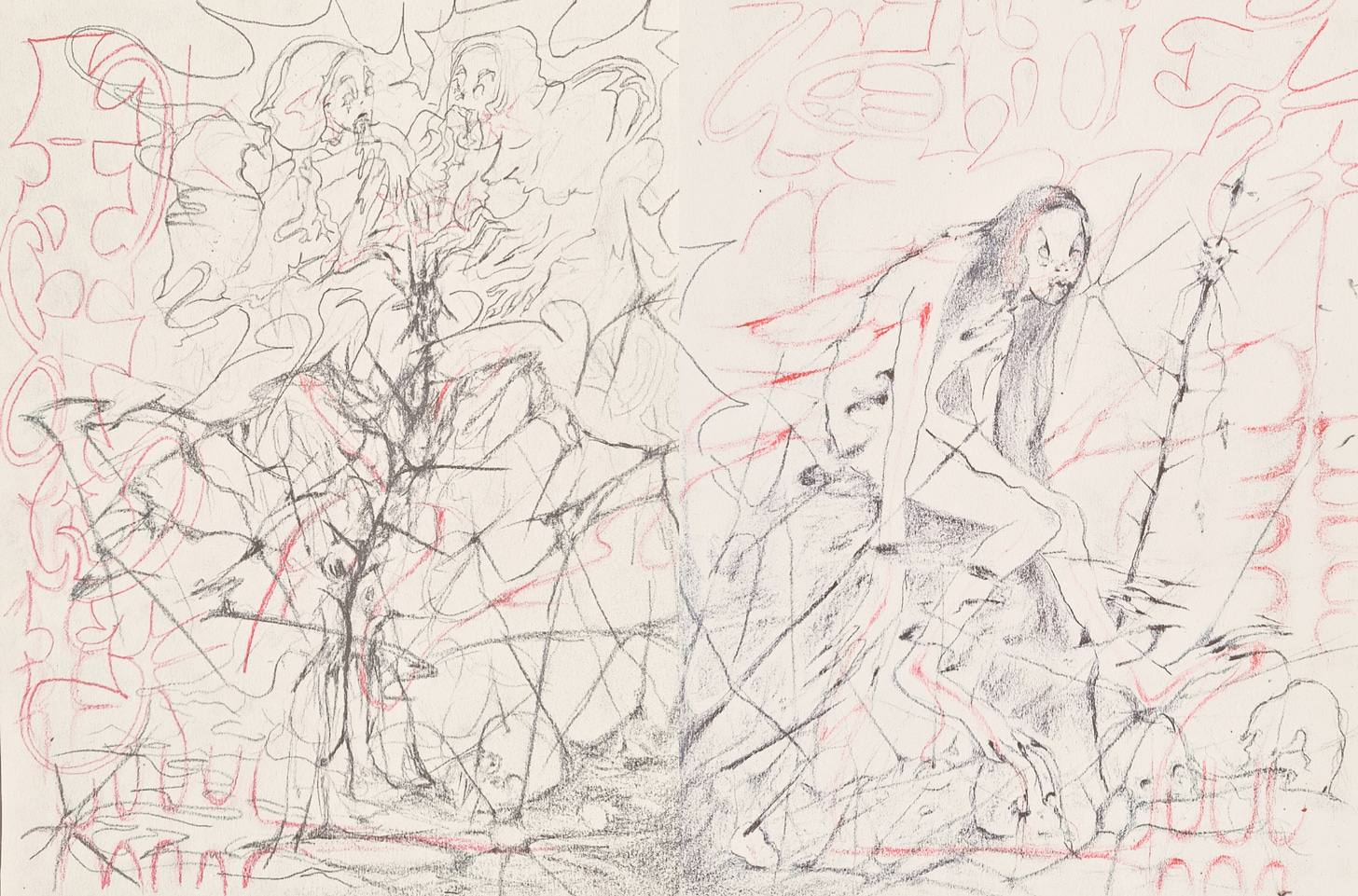

Original drawings by @fogotziita_96

Whew, this is really GOOD! Thank you for this very much needed perspective Joey, I felt this very deeply as a marginalized person.

"Maybe a malefic decan isn’t so bad if you belong to the maligned!" LOVE IT!

Great read, highly recommended!